By Anthony Brewer at BWCI

anthony.brewer@bwcigroup.com

“The priority for many schemes has become

protecting their improved funding positions”

A rapid rise in yields has changed the funding picture for many Defined Benefit (“DB”) pension schemes dramatically over the last couple of years.

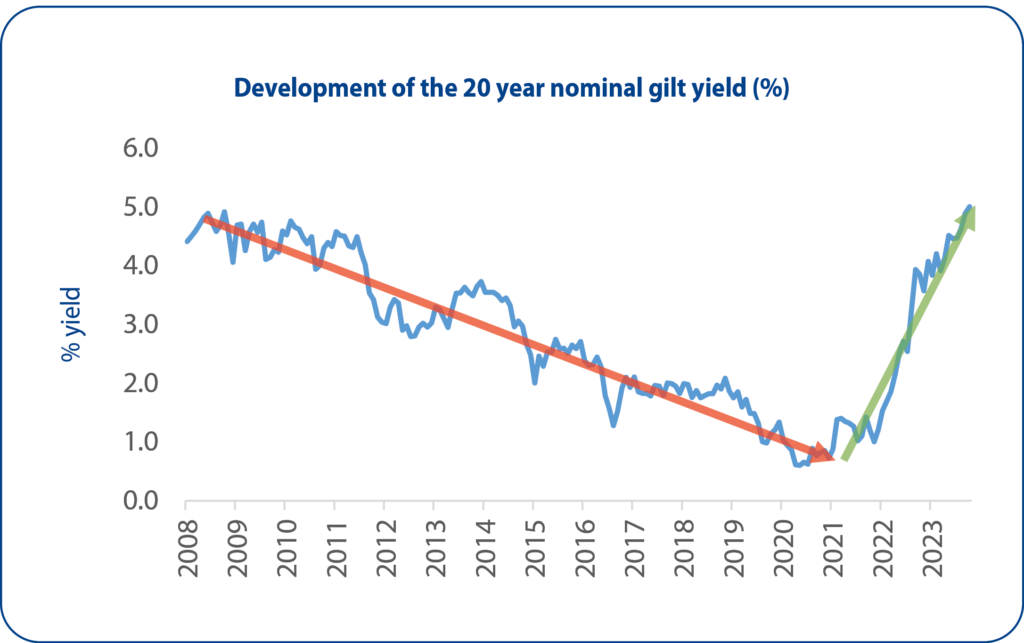

It is hard to exaggerate the speed at which the yields on UK Government bonds (“gilts”) have risen since the start of 2022, completely unwinding over a decade of persistent falls. The chart shows how yields on 20 year gilts had been falling since 2008, until a rapid turnaround in 2022.

Why yields fell

During the environment of weak economic growth and low inflation following the 2008 global financial crisis, policymakers attempted to stimulate economies with ultra-low interest rates and “Quantitative Easing”, often referred to as “QE”.

QE saw the Bank of England buying bonds in the market to reduce supply. The impact of this squeeze on availability pushed up the price of gilts. Consequently, as the income from the gilts was unaffected, the yields available to investors fell. Ultimately the outcome of QE was to make long-term lending cheaper in an attempt to stimulate investment and boost the economy.

So what changed?

In short – Inflation reached levels not seen for decades.

Demand and supply became imbalanced during (and following) covid, particularly as a result of the associated stimulus measures taken by governments around the globe. Quantitative Easing has been reversed and become “Quantitative Tightening”. This has had the opposite effect on yields, and bank rates have risen to levels not seen since 2008.

Why are yields so important for DB schemes?

The yield on long-dated gilts is often used by actuaries as the starting point for setting the discount rate when calculating the present value of a pension scheme’s liabilities. The higher the yield, the lower the present value of these liabilities. This means that you need a lower value of assets to invest today to meet the future projected cashflows, as you can now expect to receive a higher investment return in the intervening period.

The sharp increase in yields has seen the value of some pension scheme liabilities fall to around half what they were when yields on gilts were at their lowest. This change has led to funding levels increasing dramatically.

This seismic shift in market conditions in 2022 has put some DB pensions schemes into unfamiliar territory: surplus! This has led to a lot of de-risking of their investment strategies in order to maintain their strong funding level and minimise the risk of deficits emerging again in future.

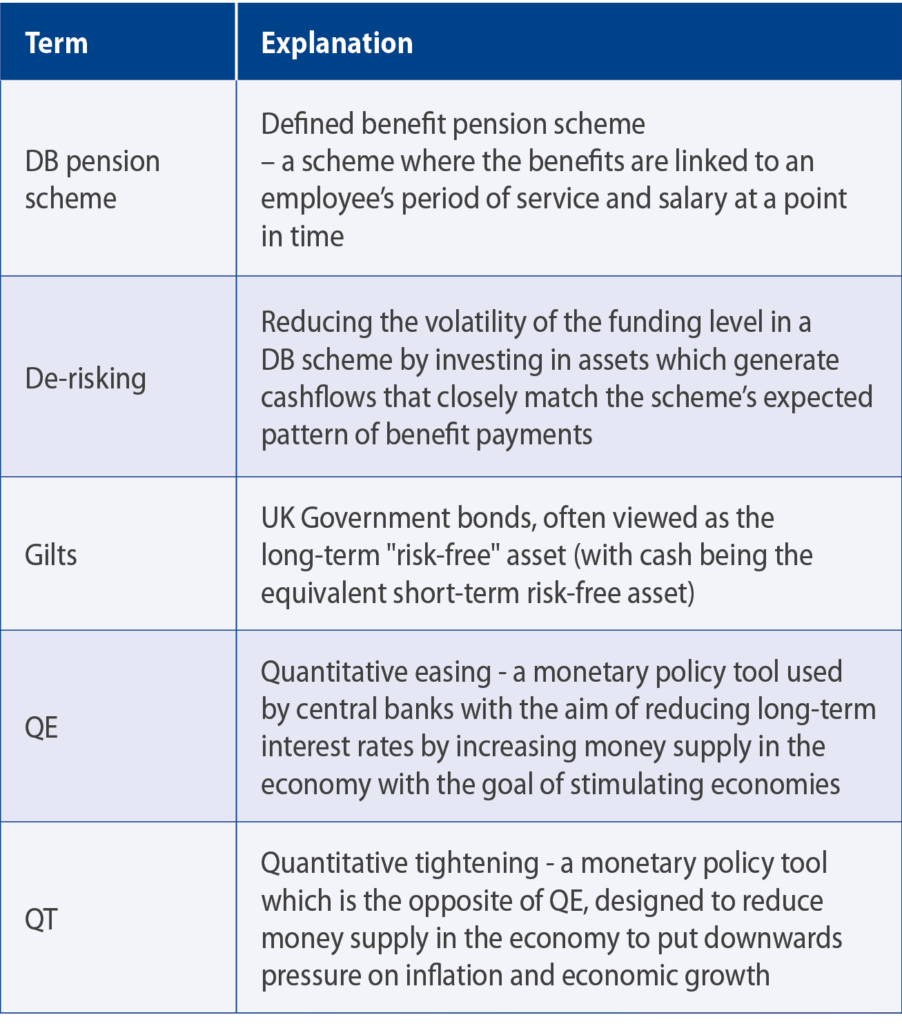

JARGON BUSTER

Why have DB schemes been de-risking?

The priority for many schemes has become protecting their improved funding positions from two key risks.

- Growth assets falling in value (e.g. an equity market crash) This has been protected by selling out of growth assets.

- Yields falling back (e.g. as a result of a significant recession where both growth and inflation return to the doldrums). This can be protected, to some extent, by buying gilts of the appropriate term (in which case, the assets are expected to increase in value in lockstep with the liabilities, ensuring no deficit arises).

Many well-funded schemes have therefore moved to a largely gilts strategy to better secure their funding position as an interim measure, whilst they consider their preferred long-term strategy.

Should schemes hold gilts long-term?

Whilst only holding gilts does tend to minimise risk versus the actuary’s assessments of the value of the liabilities, it is reasonable to explore other investment options as well, due to the potential downsides of investing entirely in gilts.

Rate of return

A gilts-only strategy generates very low returns, limiting the opportunity for the scheme’s surplus position to improve further. For schemes that still have very long investment horizons, this strategy may actually add more risk than it removes. This is because there may be unexpected demands on benefits that gilts investment would struggle to fund: for example, increasing longevity of pensioners, unanticipated State action on pensions and imperfect cashflow matching.

Paying benefits

The actuary’s basis is fundamentally a tool used to calculate the assets, and therefore contributions, a scheme is expected to need today to meet its future liabilities; it does not attempt to define the optimal investment strategy for a scheme.

For a well-funded, closed scheme, there are unlikely to be any further contributions required and therefore the actuarial basis is now less relevant to decision-making than it may have been previously. The focus for schemes which find themselves in surplus should be on meeting the benefits promised to members, including ensuring sufficient liquid assets are available to meet the benefit cashflows when they need to be paid.

What about “buy-out”?

To remove the ongoing funding risks from the sponsoring employer, a target for some well-funded schemes is to buy-out the benefits with an insurer. This is where a premium is paid to the insurer, which then invests the assets (not necessarily in gilts) and pays the benefits directly to members over the long term, whilst also generating a profit for the insurer. Simple in theory, but many (particularly smaller) schemes may find the cost and complexity of a buy-out to be a significant barrier. A buy-out would also result in the permanent loss of the potential opportunities associated with a scheme in surplus.

Making use of the surplus

There are a number of reasons why a scheme might maintain a long-term investment strategy with some upside potential. A strong funding position provides an excellent buffer for some modest investment risk to be taken. This can typically be done without any detrimental impact on the security of members’ benefits; in fact, over the long-term, it may improve the security of members’ benefits given the expectation of higher asset growth. There are several potential flexibilities such an approach may unlock:

Members’ benefits enhancements

Surplus assets can be used to provide discretionary increases during periods of high inflation when caps on annual benefit increases often bite.Return of surplus

Sponsors have often put a lot of money into a scheme, particularly so in recent years during the period of falling gilt yields. Where the rules of the scheme permit, there may be reasonable opportunities to return some of this value, allowing them to reinvest in their business or enhance benefits provided to current employees in Defined Contribution schemes, so helping to narrow the inter-generational gaps and inequalities when it comes to pensions provision.Directing capital to productive investments

Subject to consideration of their fiduciary duties, schemes could invest in assets aligned with societal, sponsor and members’ best interests. For example, these could include funding key infrastructure projects associated with decarbonising the economy, building affordable housing, improving core infrastructure. Not only can a scheme maintain high security of members’ benefits, it can also improve the world the members live in, potentially on both a global and local scale!

Long-term strategy

There is a wide range of assets that may be appropriate for a pension scheme to invest in long-term, particularly those assets which generate predictable cashflows, to ensure members’ benefits are met with a high degree of certainty. These asset classes include corporate bonds, private credit and infrastructure debt (alongside gilts). A modest allocation to growth assets may also be attractive; the larger the surplus, the more flexibility here.

Ultimately a mind-set change may be warranted, as we move from an environment where schemes presented seemingly ever-growing liabilities, as yields fell, to one where they present opportunities to generate value for members and sponsors and even the broader society.