By Anthony Brewer at BWCI

anothony.brewer@bwcigroup.com

“removing all headline investment risks for a well-funded scheme does not guarantee success”

As discussed in my previous article “Pension surpluses – what now?”, many Defined Benefit pension schemes are now in a strong funding position following a dramatic rise in interest rates in recent years. This has led to widespread “de-risking” to lock in the improved funding position (generally buying government bonds and selling growth assets, e.g. equity).

However, whilst investment-related risks (e.g. interest rate, inflation and growth assets falls) have been significantly reduced by changes in investment strategy, there remain important risks for these “de-risked” schemes to consider.

What other risks are out there?

- Longevity – Improvement in life expectancies is a core risk for pension schemes.

- Individual experience – Particularly relevant for small schemes, where a handful of members living longer than expected can significantly impact the funding position.

- Inflation basis risk – Available investments are linked to UK RPI, whereas many local schemes use a Channel Island inflation measure for benefit increases. Whilst similar over the long term, there can be divergences between the two inflation measures.

- Mismatching risks – There are a wide range of approximations and assumptions which are needed to construct a liability-matching asset portfolio. For example, pension increases are often linked to inflation with a cap (e.g. 5%) and a floor (e.g. 0%). There are no readily available assets which can exactly match this exposure. This means that even a well-matched fully de-risked pension scheme can still see funding volatility from changes in market conditions.

Unfortunately, this is not an exhaustive list of risks! Historically, schemes were often running such material investment risk (e.g. a significant allocation to equity) that these other risks were only of second order relevance, however the situation is now often reversed today.

What happens if these (or other) risks materialise?

In some cases, an existing surplus may be large enough to absorb future shocks. If not, there are two back-up options:

- Asset return – Investment growth could offset unexpected funding shocks, therefore taking some investment risk today may reduce the (more important) risk that the scheme is not ultimately able to meet its benefit obligations in full.

- Sponsor contributions – However, understandably, sponsors may be reluctant to further fund these schemes, which often have limited relevance for the current workforce, in the context of often significant historic contributions.

Generating asset outperformance involves investment risk – is this reasonable for schemes to take?

In many situations, yes, (within reason).

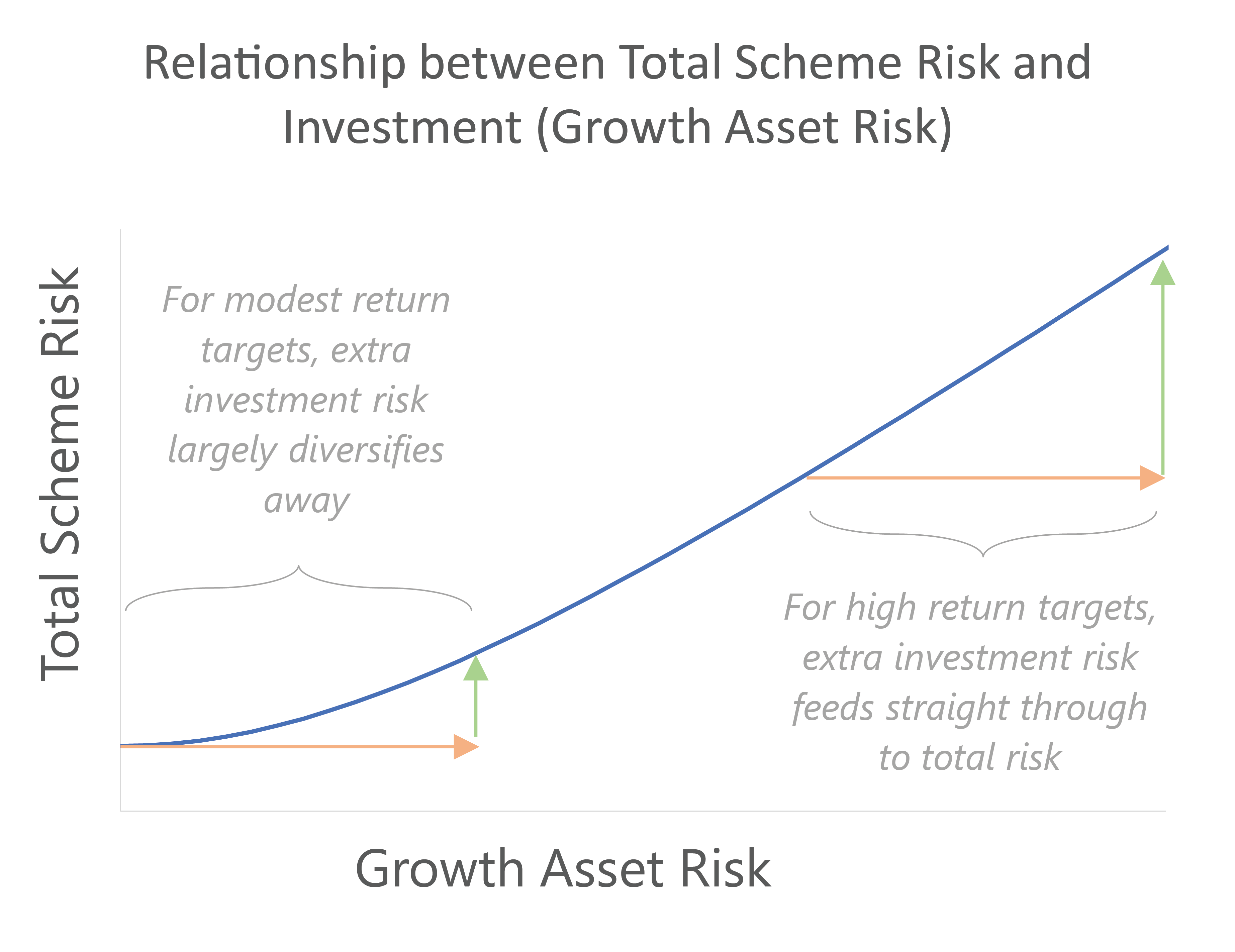

Diversification is a scheme’s friend; introducing investment risk does not increase a de-risked scheme’s total risk on a one-for-one basis (see chart for illustration, note: higher growth asset risk implies higher target investment return). Total risk includes longevity, basis and mismatching risks, which are not generally correlated with investment returns. Consequently, the chance of these risks “hitting” a scheme at the same time as an investment shock is low. It may therefore be very risk-efficient to take some investment risk.

How much investment return (and associated risk) is reasonable?

There is no one-size fits all answer, as the maturity of the scheme, risk appetite, funding position, long-term ambitions and views of the sponsor should all be considered. In general, modest exposures to more risk are likely to be reasonable for many schemes. Examples of increased risk exposure include switching some gilts into corporate bonds or investing surplus funds in growth assets.

The relevance of scheme maturity

As a pension scheme matures, the proportion of its assets paid out in benefits each year tends to increase. All else equal, this creates increasing investment spiral risk, where asset drawdowns become crystallised through the need to sell assets to meet cashflows. This is because there is no opportunity for the investments to recover their value as they will have already been sold. However, this risk can be mitigated, even when targeting investment outperformance, for example by using cashflow-matching investment strategies.

Conclusion

Ultimately, removing all headline investment risks for a well-funded scheme does not guarantee success (risks remain) and this approach may not represent the optimal long-term strategy.