By Mark Colton at BWCI

mark.colton@bwcigroup.com

“No bank maintains sufficient capital

to pay all its depositors at once.”

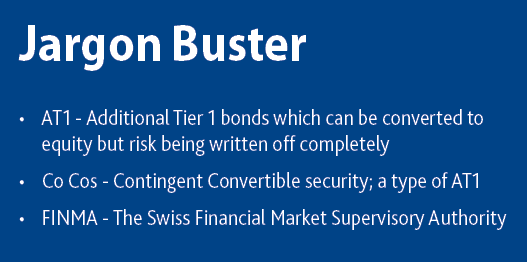

Like a tabloid journalist’s headline, “CoCo pops” was inevitable, albeit a million miles away from the sugary breakfast cereal. “CoCo”s are a type of investment, and some of them have imploded spectacularly.

What are CoCos?

A “CoCo” is a Contingent Convertible security. These have been around for a while. Their duller formal name is: Alternative Tier 1 debt.

Their creation was a consequence of the 2008 financial crisis, to protect the viability of banks in extreme circumstances. If the capital in a bank falls below a prescribed level, then the CoCo converts from a loan (secure) to an equity (risky). This reduces the bank’s liabilities and increases the capital available to meet its liquidity requirements.

Why are they in the news?

They are in the news now because they were a casualty of Credit Suisse’s collapse into the arms of its rival and saviour, UBS. Investors holding Credit Suisse CoCos saw their value go from about $17bn to zero, whilst holders of (riskier) equities came away with $3.25bn. It all sounds a bit odd.

How did this happen?

It was the weekend of 18-19 March 2023 that saw the shotgun marriage of Credit Suisse and UBS, presided over by the Swiss regulator, (FINMA). Credit Suisse was actually in sound financial condition, but there were losses of confidence in its financial security (a series of scandals including Greensill Capital, and market jitters stemming from the travails of other banks, such as SVB in the US).

No bank maintains sufficient capital to pay all its depositors at once. Indeed, a relatively small fraction is maintained in liquid capital, the rest being loaned out. A run on a bank could therefore easily make it effectively insolvent.

The documentation for the Credit Suisse CoCos showed that Swiss regulators had the right to reduce a holding’s value to zero, despite the usual priority for recompense: conventional bonds, AT1s (CoCos) and then equities.

What are investors’ reactions?

Investors representing $4.5bn of the affected CoCos have filed a lawsuit against FINMA, alleging that it did not act proportionately and in good faith. Whilst there is no challenge to the rights of FINMA to act, the lawsuit focuses instead on whether the exercise of such powers was justified.

Investors more generally were understandably nervous, with other banks’ AT1 debt falling in price. There was a rush to calm nerves from other European regulators and from the Bank of England.

Could this happen again?

Apparently the answer is “no”. But probably safer to say that CoCos generally have priority over equities, but each case will depend on the securities’ documentation and regulator.

In the meantime, new investors may wish to see a higher return on such investments to compensate them for the additional risk. The main bond market will be less concerned. It comprises government and company (non-convertible) debt.

What are the implications for pension funds?

Pension funds invest in equities and bonds, which may also include debt such as AT1s. Any significant holding in Credit Suisse’s CoCos will have reduced to zero. For Defined Benefit schemes, this means trustees will look to the employer should extra funding be required. The financial strength of the employer, its “covenant”, is important for Defined Benefit schemes, and this might have been affected if the employer had significant holdings in the affected securities.

For Defined Contribution schemes it would be the members who bear any investment losses.

Having said that, pension schemes are generally well-diversified in their investments, which insulates them against the outcomes for any one company. However, contagion was the real risk from Credit Suisse’s difficulties, and that might have been accompanied by a much louder pop!